In August, four scholars and a small group of Jewish and Muslim emerging religious leaders met to discuss the story of Joseph in the Qur’an and in the Bible. Here are four reflections, by two Muslim women and two Jewish women, about the significance of Zuleikha in the story and in their respective traditions.

Muslim reflections

I. By Asma T. Uddin

In the Qur’an, Joseph, son of Jacob, had a somewhat dysfunctional relationship with his brothers, who resented him for being the favored, most beloved, son of their father. On one occasion, Joseph’s brothers took him on a picnic and decided to get rid of him by throwing him into a well. After they left, a passing caravan happened to stop at the well, where the caravan’s water-scout found Joseph, and decided to take him to Egypt. Once there, Joseph was sold for a paltry price to a high-ranking nobleman. As the Qur’an tells us, the nobleman who bought Joseph, al-Aziz, said to his wife, Zuleikha, “Tend graciously to his dwelling, he may benefit us, or we may take him as a son.”

From the nobleman’s statements, we are led to believe that the nobleman and Zuleikha did not have any children, and that Joseph could thus have been taken as an adopted son. This is, in fact, the interpretation of many tafsir scholars. The lack of children suggests sexual intimacy may be lacking in the couple’s relationship. With the story framed by Zuleikha and al-Aziz’s relationship, the Qur’an goes on to the widely-known story of seduction and resistance:

Zuleikha felt deeply and passionately attracted to Joseph, and on one occasion, when her husband was out, Zuleikha called Joseph to her room. As soon as he entered, she locked the door and said, ‘Now come to me, my dear one.’ Taken aback by this advance, Joseph told her: ‘God forbid. My master has been generous to me; I cannot betray his trust. Those who do evil can never prosper.’ So saying, he rushed towards the door and tried to unlock it.

Zuleikha caught hold of his tunic from behind and, in the tussle, it was torn. Joseph managed to unlock the door, but only to find his master outside. Zuleikha cried: What is the fitting punishment, my master!, against one who has evil design against your wife, but prison and chastisement!

Joseph denied the charge and said that it was Zuleikha who had sought to seduce him. An advisor from the household, a lady of reputation, was asked to settle the dispute. If Joseph’s tunic was torn from the front, she said, then he was guilty; but if it was torn from the back, then Zuleikha should be held accountable. The husband saw that the tunic was torn from the back; he told his wife that she had been at fault. He asked her to seek forgiveness, for truly it was she who had sinned.

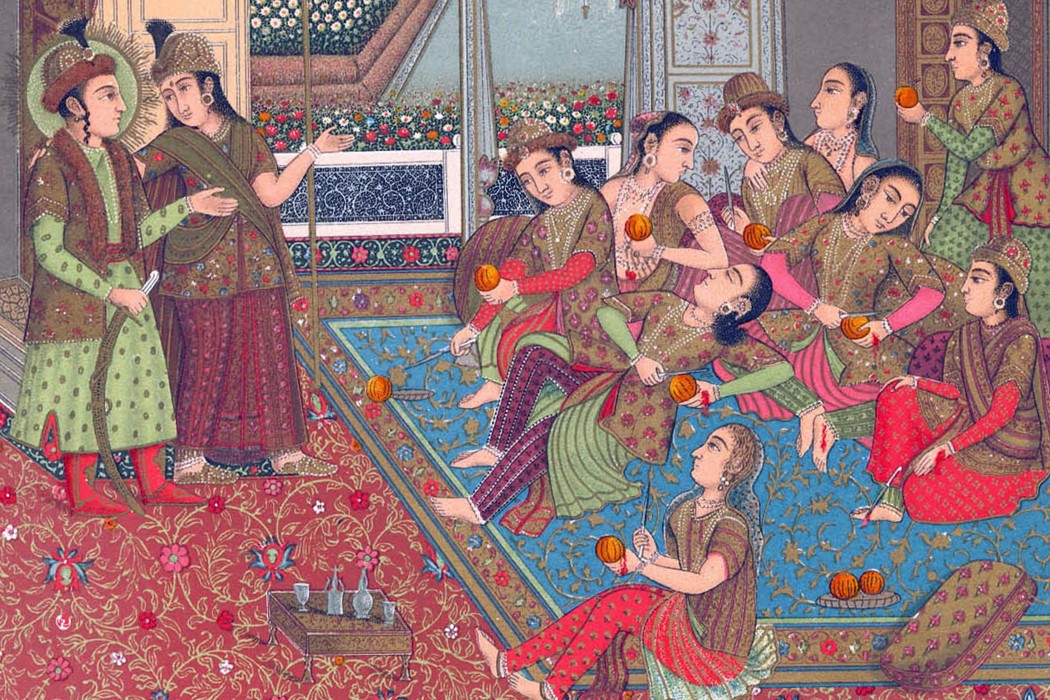

Although this account of Zuleikha’s attempted seduction of Joseph seems to lend credence to allegations all too often found in Islamic scholarly texts about the evil charms of women, it is important to note that the story was preceded by the suggestion that the Zuleikha and al-Aziz were childless, and that al-Aziz may in fact have been a eunuch. Further, as the Qur’anic story progresses, we are told that Zuleikha, when mocked by the women of Egypt for her lust, invites them for a meal. As they are holding knives in their hands to pare some fruit, Joseph walks into the room and the women end up cutting their fingers out of absolute awe over Joseph’s beauty.

The women were so struck by the extraordinarily good-looking young man that they could not take their eyes off him; in the excitement they cut their fingers with their knives in their hands. They exclaimed: O God preserve our chastity. He is not a man! He looks an angel.

Two important points are made by this bookending of the story of Zuleikha’s seduction: First, she is craving intimacy in her life, and seeks fulfillment of her basic needs. This emphasizes the reality that women, too, have sexual needs, and their sexuality is as real and as valid as men’s sexuality. Islam is often contrasted with Judaism and Christianity in its affirmation of sexuality and its articulation of both men and women’s sexual needs. Women, like men, have certain sexual “rights” in marriage which it is incumbent upon their spouse to fulfill. And the fulfillment of those rights is considered a religious duty – an act of worship, in fact. With her husband unable to fulfill her sexual rights, Zuleikha is, from an Islamic perspective, legitimately suffering, though of course the Qur’an makes clear that her sexual advances outside of marriage are prohibited.

Second, the women of Egypt’s unanimous reaction of wonder to Joseph’s beauty underscores that Zuleikha is not a representation of female guile, but of the human response to Joseph. His beauty was above subjective desires and something so absolute that the response to it was unanimous and uncontrollable. The “story of seduction” is therefore constructed to be more about Joseph’s irresistible beauty than it is about Zuleikha’s – or any female’s – charms.

II. By Homayra Ziad

As a woman reflecting on the Biblical and Qur’anic stories of Joseph/Yusuf, I find myself returning time and again to the maddening figure of Zuleikha, the wife of al-Aziz. While Zuleikha disappears post-seduction in the Biblical text, she makes two more appearances in the Qur’anic text, the last of which is a declaration of repentance. What is the significance of Zuleikha’s return in the Qur’an?

In the Qur’an, as in the Bible, Zuleikha first appears as a dyed-in-the-wool seductress. When she is rejected by the Prophet Yusuf and her actions are exposed to her husband, she becomes bitter and vengeful. She hurries to justify her trespass to the town gossips by parading Yusuf in their presence; they cut their fingers in disbelief at his beauty. She further persists in her transgression, threatening Yusuf with imprisonment and humiliation if he does not succumb. In the end, she drives him, a pure and good soul, to seek prison as his only refuge. At every step of the way, Zuleikha embodies the worst in human nature.

Yet, of all the figures in the sura of Yusuf Joseph story, Zuleikha is the most real. Yes, the Prophet Yusuf was severely tested, but at each breaking point, he was delivered to a greater glory by a sudden turn of events largely beyond his control. But there is no deus ex machina for Zuleikha; she must struggle to find herself on her own. Locked in vicious struggle with Yusuf, she is a symbol of the troubled soul crying for prophetic guidance, but scared to death of where it may take her. Zuleikha is the self, sensing its way to actualization. She models what we all go through, the mistakes we make, our pettiness and bad humor, the hurt we inflict on those we love, how we take our own pain out on those around us. Zuleikha is a flesh-and-blood human being. She is our shadow, and as such, we must claim her and love her.

In the moment of repentance, however, Zuleikha seems to be suddenly, utterly changed. She becomes a cardboard cutout, mouthing truisms. Must Zuleikha lose what makes her human in order to fully repent? But if we step back a little, we see that she does not lose herself; it is the goal itself that has changed, for the path of actualization is no less than the sublimation of self. Is it so bad to be a mouthpiece for the Truth? From this vantage point, Zuleikha has become the soul at peace in God. She has lost her “I” and instead speaks with the tongue of Truth.

Perhaps that is the greatest significance of Zuleikha’s return in the Qur’an: it completes her story, from transgression and bitterness to repentance and the painful re-turning of the self to God. Her return makes her a symbol of wholeness. Just as Zuleikha was our shadow, the unsettling depths of our nature, so she also represents our greatest hope.

Jewish reflections

I. By Rachel Barenblat

In studying the Joseph/Yusuf story as it appears in the Qur’an, the Torah, midrash and tafsir, one of the biggest revelations for me is how differently our two traditions speak of Zuleikha. Our texts agree that Joseph rises to prominence in the house of one of Pharaoh’s viziers and that the vizier’s wife makes a pass at Joseph, which Joseph refuses. But there the stories diverge.

Jews read the Joseph story as a parable about descent for the sake of ascent. Joseph descends into Egypt in order to rise in Potiphar’s (the Qur’anic “al-Aziz”) house, and descends into jail in order to rise as a servant to Pharaoh (and in order to waken to God’s providence in his life.) Thus his family and community descend into Egypt and are saved from famine, in order that when “a Pharaoh arises who knew not Joseph,” and the people are enslaved, God can liberate the Jewish community with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. This liberation is the central narrative of Jewish peoplehood: it leads us to Sinai and to the revelation of Torah, our covenant with God.

Zuleikha has only a minor role to play in this story. She exists in the narrative primarily to give Potiphar a pretext for jailing Joseph; after that, she disappears from the Torah text. When she appears in midrash (classical exegetical stories), she is often depicted through an uncharitable lens.

One midrash declares that Zuleikha speaks “like an animal” when she commands Joseph to “lie with me.” Reading that text, I see the early roots of the western literary trope of the sexually ravenous “Other,” the foreign woman whose wiles put the hero’s virtue at risk. Another midrash shows Joseph “unmanned” — the spirit may be willing, but in the critical moment he finds his body incapable of committing sin, thanks to God’s grace. It seems to me that both of these texts show Zuleikha in a negative light.

But classical midrash was written by men, who have their own fears and agendas. Over the last few decades, however, a tradition of contemporary feminist midrash has arisen in Judaism. Jewish women have written stories and poems which give voice to Eve and Lilith, Sarah and Hagar, Rebecca and Rachel and Leah. I look forward to the day when Jewish women reclaim Zuleikha, too.

II. By Marion Lev-Cohen

In the Quran and hadith as well as the Bible and Midrash, Zuleikha’s story is tied together with Joseph’s. This connection, among others, invites us to examine the intriguing differences between these two traditions regarding the role and personality of Joseph. In brief, the Yusuf of the Quran is a blemish-free individual, a virtuous Prophet. Throughout the sura containing the Yusuf story, his behavior is impeccable. This portrayal stands in direct contrast to the Biblical narrative, which portrays Joseph as a deeply flawed, vain, and narcissistic youth who gradually learns to be aware of other people’s needs and feelings. Joseph’s journey to Egypt is a metaphor for the psychological journey he takes as he moves from an immature naar (interpreted as youth, but also as naïve) to the selfless and forgiving brother we meet in his later encounter with his brothers as the vizier of Egypt.

In the Bible, Potiphar’s wife (the Qur’anic “Zuleikha”) is portrayed as the consummate seductress of the young and beautiful Joseph. She joins the ranks of the other seductresses who tempt virtuous men. We recall Adam and Lilith, Samson and Delilah. In contrast to the Qur’an, Potiphar’s wife is not displayed as a complex character blinded by Joseph’s beauty, nor does she finally confess and repent for her sins. She is merely a foil for Joseph’s virtue.

This characterization as the evil temptress has continued into early rabbinic times. Potiphar’s wife is likened to an animal because of her indelicate way of commanding Joseph to lie with her. “But this one [Potiphar’s wife] was like a beast: ‘Lie with me!’” (Gen. Rabbah 87:7).

On the other hand, Midrash Tanchuma, a 6th century homiletic work, is more even-handed in its description of the main protagonists. Both Joseph and Potiphar’s wife are more complex and nuanced characters. Potiphar’s wife attempts to exonerate herself by demonstrating the irresistible nature of Joseph’s beauty. Unlike the other traditions, in this midrash, Joseph is said to bear responsibility for all the evils that befell him because of telling tales about his brothers.

As modern feminist scholars seek to plumb the clues to understand the role women played in the Bible, their research of the many narratives and homilies written about the Yusef/Joseph story generate varying interpretations of the relationship between Joseph and Potiphar’s wife. May the richness of the stories of our ancestors continue to serve as guides for us in our modern day relationships.

Asma T. Uddin is Editor-in-Chief of Altmuslimah.

Homayra Ziad is Assistant Professor of Religion at Trinity College, where she teaches courses on Islam. Her scholarly interests include intellectual and cultural trends in Muslim India, theoretical Sufism, women’s religious production, theologies of pluralism, and Qur’anic hermeneutics.

Rachel Barenblat is a student in the ALEPH rabbinic program. She holds an MFA in Writing and Literature from Bennington, and is author of three chapbooks of poetry, most recently chaplainbook (Laupe House Press, 2006), a collection of poems arising out of hospital chaplaincy work.

Marion Lev-Cohen is in her last year of rabbinical school at HUC/JIR, and is a clinical social worker by training.. She currently serves as the rabbinic intern at Central Synagogue in New York.